Introduction

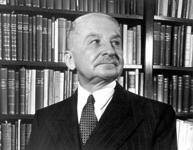

In the pursuit of science little can be said to be of greater importance than the epistemology employed. In this regard the epistemology of the Austrian School of economic thought has been roundly criticized and rejected by mainstream economists.1 This reaction was primarily due to Ludwig von Mises's firm stand on apriorism and the claim that praxeology, of which economics was the most developed discipline, was a new science, unconnected to previously acquired knowledge (Mises, 1966, 1-10).| English: Ludwig von Mises in his library (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

With Smith's introduction of fallibilism into Mises's system, some of the distance between it and Karl Popper's concept of conjectural knowledge was reduced. This reconciliation has been visible in a number of efforts that attempt to bring Mises's approach into the methodological housing of Popper and other philosophers of science, notably Imre Lakatos.3 More on that in another post; but, at this moment we have another issue to address — Mises's claim that economics, and its encompassing science, praxeology, are new sciences unconnected with previous knowledge. This claim did not sit well with those who believe all knowledge to be connected and do not have an anthropocentric view of the universe.

The Origins of Action

Mises went to great lengths to deny that human action is in any way related to action in our evolutionary ancestors, even stating that "The newborn child is not an acting being," and that "Beings of human descent who either from birth or from acquired defects are unchangeably unfit for any action... are practically not human" (1966, 14). To do so seems to strike at the very notion that we have evolved from species that have less flexibility than we, and from whom we do not stand apart in the universe. In this context Mises formulated what has become known as the action axiom — man acts, aiming at the improvement of his situation relative to his values (1966, 13-14).| English: Karl Popper in 1990. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

At this point we must ask, "what problem is being solved?" The answer lies in the action axiom — the problem of improving the situation, or survivability, of the organism. Each organism acts, in the way it understands, to improve its situation.4 It appears that Popper's statement stands as a powerful axiom — possibly the basic axiom of biology — in support of Mises's more specific one and reveals biology as the epistemological basis of economics. In fact economics is not separated from all of the other sciences, but is an outgrowth of biology.

This conclusion would most likely suit Edward O. Wilson who said "It is in biology and psychology that economists and other social scientists will find the premises needed to fashion more predictive models, just as it was in physics and chemistry that researchers found premises that upgraded biology" (1998, 206); however, Wilson did not expect the basic premise to come from a philosopher or support the Austrian methodological approach.

We do not argue here that economics has that much to learn from biology, although Wilson certainly believes it does. Economics is clearly a human science — the most fundamental theorems depend on activities that are observable only in humans. What we do argue is that biology supplies an axiom that is fundamental to all life that strengthens Mises's action axiom, supporting it with what Rothbard would have called a "law of reality rather than a law of thought" (1957).

At this point we must question why Hayek did not see this connection. He knew, and was friends with, both Mises and Popper, as well as having a deep understanding of their work. He also came from a family of biologists. His father was a serious botanist as well as being a doctor, and Hayek helped him with botanical work and attended society meetings (Ebenstein, 2001). At this point we can only speculate, but he may have seen Mises's and Popper's works as irreconcilable and never even contemplated a reconciliation of their views. Perhaps he was reluctant to start down a path that could have resulted in the loss of one or both of his closest intellectual associates. In any case, it is unfortunate that a person of his stature did not complete Mises's work by linking economics with the rest of knowledge.

Conclusion

With the modification of Mises's viewpoint on action yet another objection to the epistemology of the Austrian School can be overcome. This modification is hardly a blow to Mises's overall system as it supports, rather than rejects, his action axiom. At the same time it ties economics more closely to the sciences, a goal that we can only believe Mises would have supported.1 See (Blaug, 1980, 81-2) and (Samuelson, 1964, 736).

2 Mises wrote extensively on methodology and epistemology, producing a volume of essays in 1933 that was later translated into English (Mises, 1960) and his final published book (Mises, 1962).

3 See (Champion, 2013), (Di Iorio, 2008) and (Rizzo, 1983).

4 This is not to say that there is some super-human intelligence in operation, but that natural processes have been evolutionarily selected that make the organism's choices the most likely to succeed.

Bibliography

Blaug, M. (1992). The Methodology of Economics: Or how economists explain (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Champion, R. (2013, March 11). The Common Ground of Parsons, Mises and Popper in the 1930s: The Action Frame of Reference, Praxeology and Situational Analysis. Retrieved from the Rathouse: the philosophy site of rafe champion: http://www.the-rathouse.com/EvenMoreAustrianProgram/Convergence.html

Di Iorio, F. (2008). Apriorism and Fallibilism: Mises and Popper on the Explanation of Action and Social Phenomena. Nuova Civiltà delle Macchine(2). Retrieved March 11, 2013, from http://www.imtlucca.it/whats_new/_seminars_docs/000195-Di_Iorio_MISES_and_POPPER.pdf

Ebenstein, A. (2001). Friedrich Hayek: A Biography. New York: Palgrave for St. Martin's Press.

Mises, L. v. (1960). Epistemological Problems of Economics. (G. Reisman, Trans.) Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Co., Inc.

Mises, L. v. (1962). The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science: An Essay on Method. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Co., Inc.

Mises, L. v. (1966). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (3rd revised ed.). Chicago: Henry Regnery.

Popper, K.R. (1972). Epistemology Without a Knowing Subject. In K.R. Popper, Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach (pp. 106-52). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rothbard, M.N. (1957). In Defense of 'Extreme Apriorism'.Southern Economic Journal(23), 315-20.

Rizzo, M. J. (1983). Mises and Lakatos: A Reformulation of Austrian Methodology. In I. M. Kirzner (Ed.), Method, Process, and Austrian Economics: Essays in Honor of Ludwig von Mises. New York: Lexington Books. Retrieved March 11, 2013, from http://mises.org/books/methodprocess.pdf

Samuelson, P.A. (1964, September). Theory and Realism: A Reply. The American Economic Review, 54(5), 736-9. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1818572

Smith, B. (1996, Spring). In Defense of Extreme (Fallibilistic) Apriorism. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 12(1), 179-192.

Wilson, E. O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

4 comments:

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. Your posts are very clear and straight to the point and I really appreciate that.

Thank you for your kind words!

This blog post provides an interesting perspective on Mises's theory and how it relates to other philosophical ideas.

Thanks for your comment, Jean. Yes, at the moment that is the major thrust of my project, especially to connect praxeology with the philosophy of biology, which faces similar challenges. Thanks for coming by!

Post a Comment